By Gayne C. Young from Field Ethos

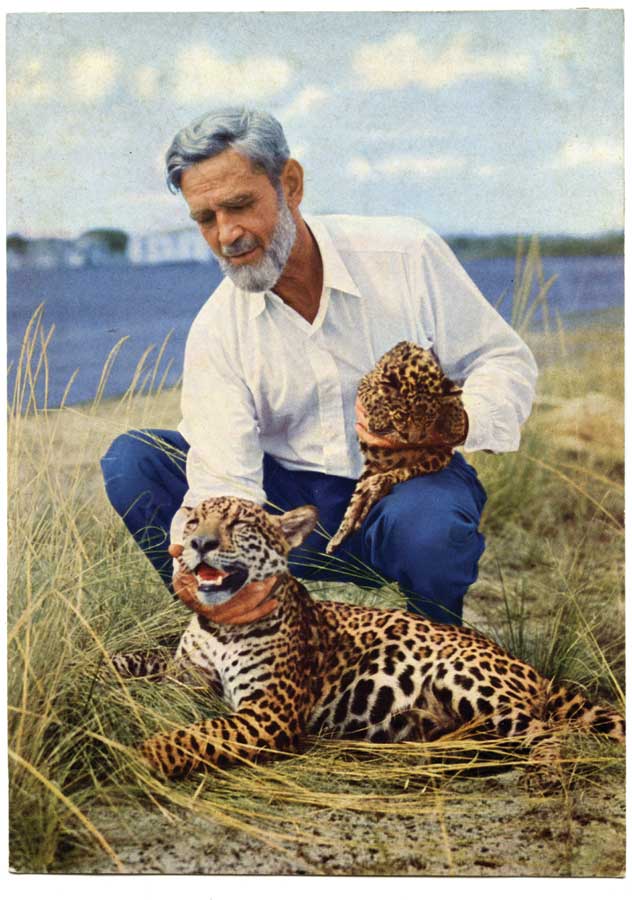

Alexander “Sasha” Siemel took over 300 jaguars in his hunting career. Mostly with a spear. Alone and deep in the jungle. Usually by getting the 250-pound cats to charge him.

Yeah, you read that right. He was as badass as men come.

Born in the small European country of Latvia in 1890, Siemel hopped a steamer to the United States in 1907 at the age of 17. Likely running from some trouble, he moved to Argentina two years later before calling Brazil home in 1914 where he took a job as a gunsmith in the jungly diamond mine villages deep within the Mato Grosso region. There, he met a drunken native named Joaquim Guato who showed him the ways of the tigrero–a person who hunts tigres (jaguars) with only a spear.

Sasha later said of his training, “… I learned the art from a poor native who had nothing but a homemade spear, where I had my high-powered rifle. But I do think I was a good pupil and will admit that it calls for experience and judgment.”

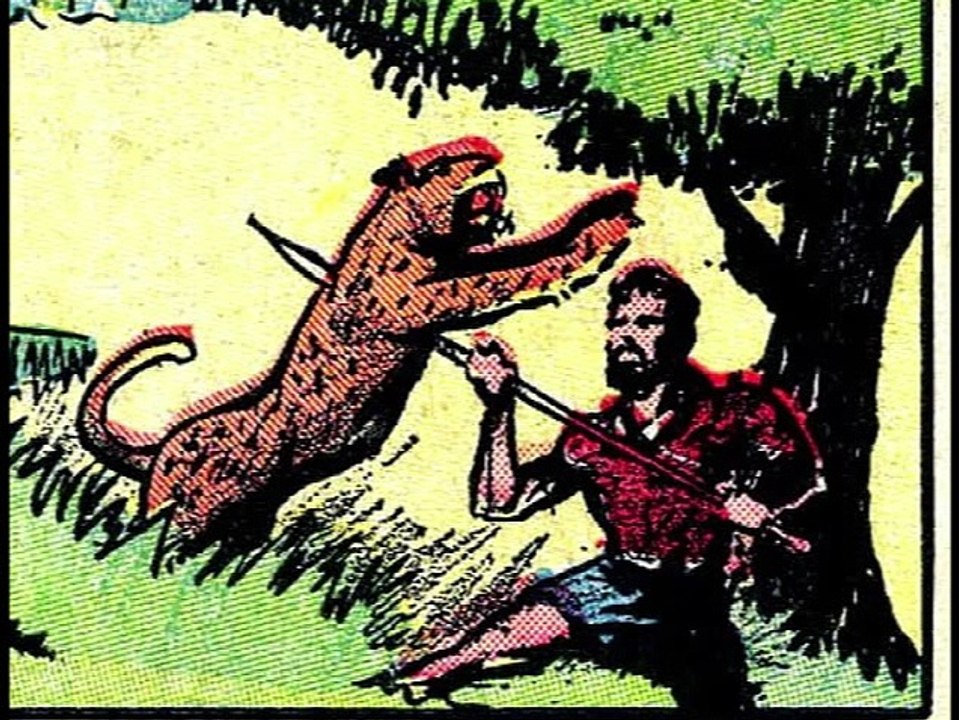

That “experience and judgment” part holds especially true, as hunting jaguar with a spear requires that the jaguar actually charge the hunter in order to be killed.

Joaquim taught Siemel that spears were made for thrusting, not throwing, and that to let go of the spear meant certain death. Guato also taught Siemel that the best way to kill a jaguar was to bay it with dogs, then, when the distance is closed to within feet of the animal, to entice it to charge by taunting it. And while that fearsome, lightning-fast leap or low-charge brought forth the momentum that helped drive the spear home, a miss, slip, or trip during the charge meant a gory, albeit quick, death in the forest. No doubt, Siemel’s wrestling, boxing and street fighting experience helped him as well, for once a man becomes engaged with an enraged cat that can easily haul 400-pound caimans (Amazon alligators) up trees, the combatants are locked into a violent fight for life and death like few can imagine.

Siemel’s spear was known locally as a zagaya that measured 7 feet in length. This specialized weapon has a thick wooden shaft to accept the tremendous energy of a charging cat; it’s tipped by a broad, double-edged, razor-honed spear point. Between the point and the shaft is a metal crossbar, key to its design, that prevents an impaled cat from running up the spear and killing the spearman. Siemel later said that in many situations where visibility in the jungle is measured in feet, the spear was preferred over the firearm because, if used with skill, it could be used to keep the cat off a man, whereas the firearm was only good for one shot.

On Siemel’s first hunt with Guato, Siemel was about to shoot a treed puma, but before he could pull the trigger the cat jumped from the tree at the exact same moment Guato’s greatest dog, Dragao, lunged at the cat. The cat, Dragao and Guato’s spear converged at once, killing both Guato’s dog and the puma. Although Guato was devastated by the loss of his best companion, he could see the passion for the hunt in Siemel’s eyes; when they returned to Guato’s hut, the indian produced two other dogs and presented one to Siemel. They would hunt the next day, and kill a tigre. Siemel was hooked.

Siemel moved to Brazil’s lawless Pantanal de Xarayés (Pantanal Region) where he became a hunting guide and a spear for hire to ranchers losing cattle to jaguar. Siemel killed his first jaguar as a professional in 1925. This feat made him the first white man to do such. Siemel killed a reported 31 jaguars in the late 1920s and early 1930s. The most dangerous and famous of these was a man-eater named Assassino.

Meaning assassin in Portuguese, Assassino was responsible for killing at least one man, between 300 to 400 cattle, and numerous dogs. Siemel later wrote that Assassino killed dogs by learning to, “…draw them in pursuit through the tall marsh grass and then circle and crouch behind his own trail, springing at the dogs as they ran by. One sweep of the razor claws would destroy a dog, and then the cat would lope on, repeating the maneuver on each dog that followed. It was this trick that gave the jaguar his name—Assassino.”

Clever cat.

Ranchers, hunters, and vaqueros alike had all tried to kill the famed cat and failed. When a hunter named José Ramos went after him with a muzzleloader, Assassino circled back on his trail only to take the man from his horse. One lightning-fast bite to the skull ended his life. Siemel found his body the next day in his search for the famed cat. With Ramo’s freshly killed body as bait, it didn’t take Siemel long to find the notorious assassin.

Siemel and his dogs trailed the cat to a narrow opening. The monstrous animal lunged, but Sasha caught him in the neck with his spear. The cat broke free from the tip, knocking Sasha off balance and to the ground. He scrambled to his feet just as the huge cat lunged again. But Sasha thrust his spear forward to meet the animal and caught him once more in the neck. A frenzy of thrashing pain and taunt muscle spun the animal toward Sasha as the man fought to push himself and the spear forward, finally managing to drive the metal tip downward and into the jag’s enormous chest. Blood frothed and spurted, taking with it the cat’s strength and giving promise the melee would soon end. Only when the cat fell and his strength returned did Siemel realize just how large the animal was. At over 10 feet (tail tip to nose) and over 300 pounds in weight, the man-killer was one of the largest cats he had ever seen, let alone killed.

In 1929, Siemel guided author/explorer Julian Duguid and two of his friends through the Brazilian jungle. Duguid wrote of this adventure and of Siemel’s history and skill as a jaguar hunter years later in his 1931 book “Green Hell.” This book marked the first time Siemel’s moniker of “Tiger Man” ever appeared in print. Duguid used the name as the title of his biography of Siemel that was released in 1932. Given the popularity this brought Siemel back in the civilized world, Duguid encouraged the jaguar hunter to take advantage of the situation.

For more than three decades afterward, Siemel’s exploits appeared in books, articles, and even in the 1937 movie Jungle Menace with Frank “Bring ‘em Back Alive” Buck. Siemel wrote for National Geographic, Colliers, Field & Stream, and Argosy and was the subject of articles appearing in Life, Reader’s Digest, and The New York Times. Time magazine profiled the famed hunter an astonishing seven times between the 1930s and 1950s. A movie about his life starring John Wayne and Ava Gardner was to be made in the 1960’s but was canceled due to the high cost of insurance necessary to film on location in the Brazilian jungle.

Siemel lectured worldwide, spoke seven languages, advertised for Imperial whiskey, appeared in cartoons, guided and hunted. While lecturing, he met a hot young co-ed 30-years his junior, photographer Edith Bray, whom he married and raised a family with. He opened the Sasha Siemel Museum and Store in Perkiomenville, PA, in 1963 as a place to educate and to display mementos of his life. Siemel’s fame continued until he died peacefully at age 80 on February 14, 1970.

Siemel was perhaps the last badass hunter to be idolized by the mainstream media. He hunted jaguars and risked it all, solo in the world’s most formidable jungle, not for fame but for pure adventure.

Fascinating story. I’ve heard and read about him in the past. Truly a one of a kind hunter.